Ye olde Reliable Data Structures and Their Controversial (Write) Access.

Using objects as data structures is an established practice that generates many problems associated with the maintainability and evolution of software and misuses brilliant concepts that were stated five decades ago. In this first part we will reflect on the writing access of these objects.

In his classic 1972 paper, David Parnas defined a novel and foundational concept for modern software engineering:Information Hiding.

The rule is straightforward:

If we hide our implementation we can change it as many times as necessary.

Prior to Parnas’ paper, there were no clear rules on information accessing and it was not a questionable practice to dive into data structures, penalizing any change with dreaded ripple effect.

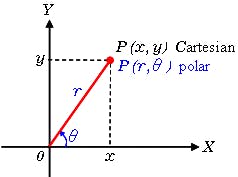

Let’s see how to model a Cartesian point:

Point Struct

Any software component that manipulates these points will be coupled to saving values as Cartesian x and y coordinates (Accidental implementation).

Since it's just a data structure without operations, the attribute’s semantics will be different according to every programmer’s criterion.

Hence, if we want to change the accidental implementation of the point to its polar coordinates analogous:

Polar Point

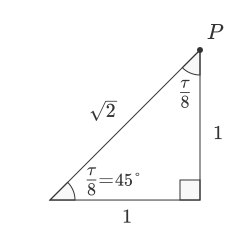

Same point can be represented in two different ways

The polar representation (√2, π/8) is equivalent to the Cartesian (1, 1)

Since it is the same point in real world, it must necessarily be represented by the same object in our bijection.

Bijection always depends on the subjectivity of the aspects we are trying to model. In order to draw a polygon, the Cartesian (1, 1) and polar (√2, π/8) points are the same point.

The case of trying to represent several possible mathematical representations would be different if we were programming Wolfram semantics. In such case representation is part of the problem se they would be modeled by different objects.

The solution is simple: Hide the internal representation.

As Parnas predicted, many of the code maintainability issues were fixed by encapsulating the decisions within the modules that define them. This is what the magnificent paper is all about.

The next evolutionary step

Upon object-oriented programming arrival, the concepts of encapsulation and information hiding were taken to an atomic extreme. We are no longer talking about encapsulating within a module but within the same object.

Returning to the previous example, we move from:

towards representation change:

A good design is one in which objects are coupled to responsibilities (interfaces) and not representations.

Therefore, if we define a good point interface, they can arbitrarily change their representation (even on runtime) without propagating any ripple effect.

when representation changes …

… everything continues to work correctly.

Algorithms and Data

If we were working with the old rule:

programs = algorithms + data structures

… then we could build excellent software with setters and getters.

This article assumes that we are eager to build, with declarative objects, models where implementation hides behind the objects’ responsibilities.

These responsibilities will be the same in the bijection between these objects and the real world.

Involution

Despite the benefits listed in the examples above, the current state of the art shows us many problems related to coupling and ripple effects. Most are generated by the ingrained habit of using setters and getters (or simply: accessors).

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash

Let’s look at setters and getters as separate problems.

Setters

Changing the internal state of an object violates the principle of immutability. This is discouraged since, in the real world, objects do not mutate in their essence.

The only method allowed to write to attributes is atomic initialization. From then on, the variables should be read-only.

If we stay true to bijection, we will notice that there are never messages with the form setAttribute..() in the real world. These are implementation tricks programmers use, and they break good models.

We will never be able to explain to a business expert what responsibility these methods have from the name.

Let’s imagine a polygon as a data structure.

Let’s assume that the polygon has at least three vertices.

Being a data structure, we cannot impose such restrictions.

Using our amazing IDE with automatic code generation, we add the setters and getters to it.

Let’s try adding the constraint on the number of vertices in the constructor:

From now on, it will be impossible to create a polygon with less than three sides, thus fulfilling the bijection with the real world of Euclidean geometry.

Unless we use our setter …

Nothing prevents us from running this code:

At this point we have two options:

- Duplicate the business logic in the constructor and in the setter.

- Eliminate the setter permanently, favoring immutability

In case of accepting the repeated code, the ripple effect begins to spread when our restrictions grow. For example, if we make the precondition even stronger:

Let’s assume that the polygon has at least three different vertices.

The correct answer, according to our design axioms, is the second.

Repeated or absent logic of invariant verification

Many objects have invariants that guarantee their cohesion and the validity of the representation to maintain real-world bijection. Allowing partial setting (an attribute) would force us to control representation invariants in more than one place, generating repeating code, which is always error-prone when modifying a reference and ignoring other references.

Code generated without control

Many development environments give us the possibility to automate the generation of setters and getters. This leads to new programmers generations thinking it is a good design practice, generating vices that are difficult to correct.

This facility spreads the problem, having this tool gives the feeling that it is an accepted practice.

Recommendations

- Do not use setters. There are no good reasons for doing so.

- Having methods named setSomething… () is a code smell.

- Have no public attributes. For practical purposes, it is like having setters and getters.

- Have no public static attributes. In addition to what is mentioned above, the classes should be stateless and this is a code smell showing a class that is used as a global variable.

- Avoid anemic objects (those containing just attributes without responsibilities). This is a code smell hinting at some missing object on the bijection.

Conclusions

Using setters generates coupling and prevents the incremental evolution of our computer systems. For the arguments stated in this article, we should restrict its use as much as possible.

The Getters

As with setters, getters are discouraged. We develop this topic in depth in this article:

Part of the objective of this series of articles is to generate spaces for debate and discussion on software design.

We look forward to your comments and suggestions on this article.

This article is also available in Spanish here.