Meta-programming is magic. That is the main reason why we should not use it. There are many dire consequences on the horizon.

The same happens with meta-programming as with design patterns:

There are states of excitement that all programmers go through. What state are you in?

We get to know them.

We don’t understand them.

We study them thoroughly.

We master them.

We read the bible that tells us that patterns are everywhere.

We abuse them thinking they are our brand new silver bullet.

We learn to avoid them.

Magic is at hand

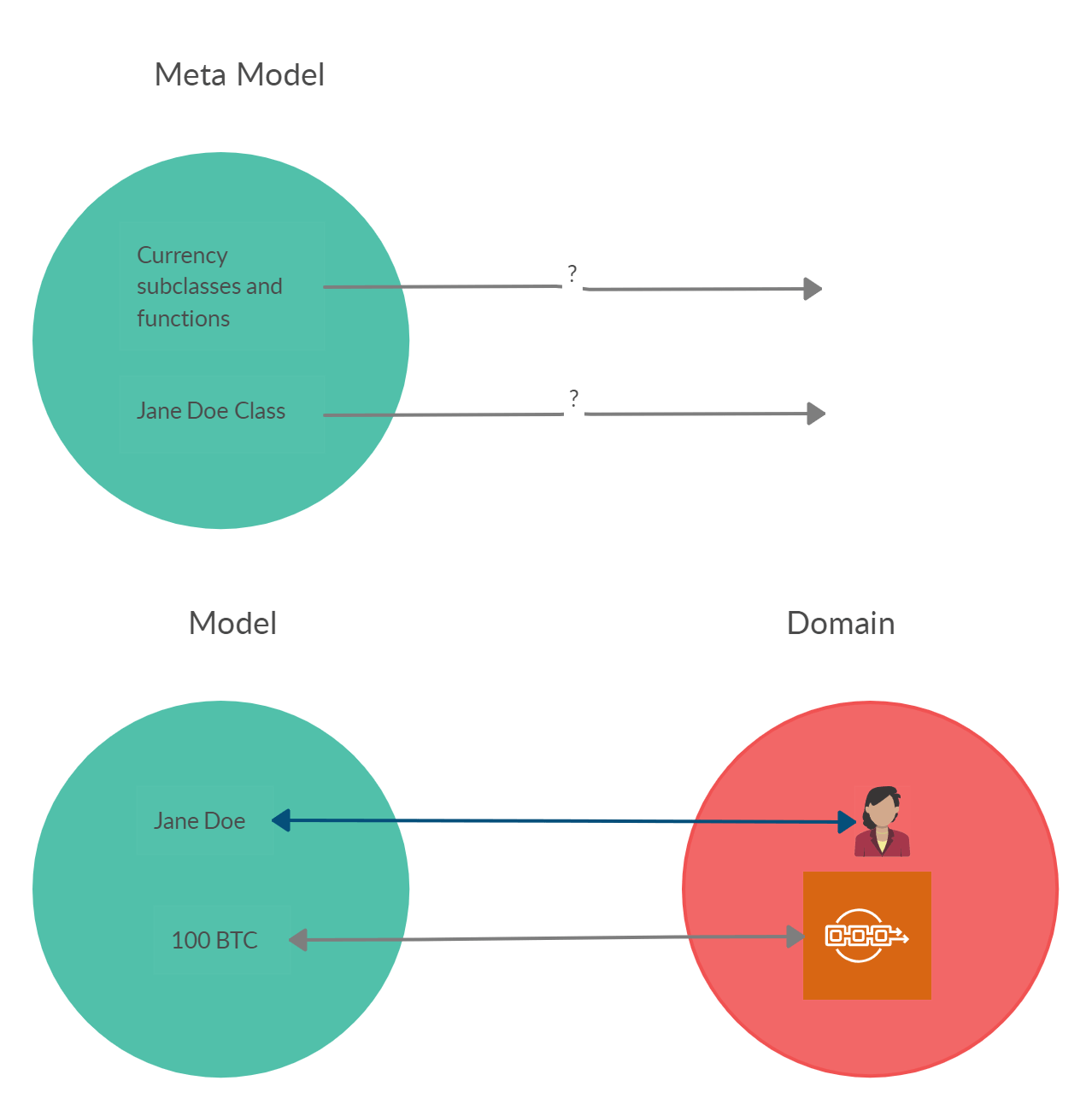

When we use meta-programming we speak about the Metalanguage and the Meta Model. This involves increasing the level of abstraction by speaking above the objects in the problem domain.

This extra layer allows us to reason and think about the relationship between the entities of reality in a higher-level language.

In doing so we break the bijection we must use to observe reality since in the real world there are no models or meta-models, only business entities that we are speaking about.

When we are attacking a business problem in real life, it is very difficult for us to justify references to meta entities because such meta entities do not exist, which means that we do not remain faithful to the only rule of a bijection between our objects and reality.

The metamodel is not present in real-world

The metamodel is not present in real-world

It will be very difficult for us to justify the presence of such extra objects and such nonexistent responsibilities in the real world.

Programmers like to think about our models. This is good practice because it allows us to search for generalizations as long as they exist in that real world.

Open but not so much

One of the most important design principles is the open/closed statement belonging to the definition of solid design. The golden rule states that a model must be open for extension and closed for modification.

This rule is still true and it is something that we should try to emphasize on our models. However, in many implementations, we find that the way to make these models open is to leave the door open using subclassing.

As an extension implementation, the mechanism seems very robust and very good at first glance, but it generates the only problem we can have in software development:

By linking the definition of where to get the possible cases, an innocent reference to a class and its subclasses appears, which is the part that could dynamically change (The extension).

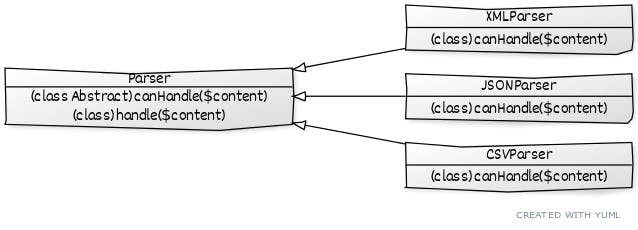

Polymorphic Parsers Hierarchy

Polymorphic Parsers Hierarchy

The algorithm asks the Parser class to interpret certain content. The solution is to delegate to all its subclasses until one of them accepts that they can interpret it and is in charge of continuing with that responsibility.

This mechanism is a particular case of the Chain of Responsibility design pattern.

However, it has several drawbacks:

Generates a dependency to the Parser class, which is the entry point for this responsibility.

It uses sub-classes with meta-programming, therefore, since there are no direct references, their uses and references will not be evident.

As there are no references and uses, no direct refactoring can be carried out, know all their uses and avoid accidental deletions.

This stated problem is common to all white box frameworks. The best known and most popular of them is the xUnit family and all their derivatives. Classes are global variables and therefore generate coupling and are not the best way to open a model. Let’s see an example of how you can open it declaratively using the Open/Closed principle:

1 We remove the direct reference to Parser class

2 We generate a dependency to a parsing provider using Dependency Injection (Solid’s D).

3 In different environments (production, testing, configurations) we use different Parsing providers and we do not connect to them belonging to the same hierarchy.

4 We use declarative coupling. We ask these providers to realize the ParseHandling interface.

Without references, there is no code evolution

Photo by John Doyle on Unsplash

The most serious problem we have when using meta-programming is having dark references to the classes and methods that will prevent us from all kinds of refactorings and therefore will prevent us from growing the code unless we have 100 % coverage.

By losing the coverage of all possible cases we might lose some use case that is referenced in an indirect and obscure way and will not be reached by our searches and code refactorings generating undetectable errors in production.

The code should be clean, and transparent, and have as few meta-references as possible that are not reached by someone who can alter that code.

Let’s see an example of a dynamic function name construction:

If we are in a client configured in Spanish, the above call will invoke the getLanguageEs() method

The problem with this dark reference is the same as mentioned in the parser example. This method has no references, cannot be refactored, cannot determine who uses it, what is its coverage, etc.

In these cases, we can avoid these conflicts with an explicit dependency (even using mapping tables or hardwired references) without meta-programming black magic.

The exception defines the rule

We have already shown that using meta-programming to refer to our real-world entities violating the principle of a bijection is a bad practice. So what should we use it for?

When we run a simulation we must stay as far away from accidental non-business aspects as possible. Among these aspects are:

1 Persistence.

2 Entity serialization.

3 Printing or ‘display’ in user interfaces.

4 Testing or assertions.

These problems belong to the orthogonal domain of the computable model and are not particular to any business. Interfering with the responsibilities of an object is a violation of its contract and its responsibilities, therefore instead of adding ‘accidental layers’ of responsibilities, we can do it using meta-programming.

Not my responsibility

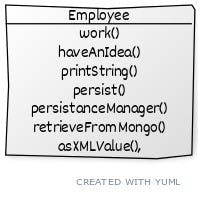

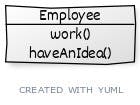

Let’s imagine how to model a real-life entity used:

Too many accidental responsibilities

Too many accidental responsibilities

If we stay true to our one-design rule, the first two functions are essential to mastering the problem and the last are not business responsibilities. Therefore they should disappear:

Just essential responsibilities

Just essential responsibilities

Using meta-programming to fulfill such accidental responsibilities for accessing such objects ensures the purity of your protocol.

However, it does bring coupling and encapsulation violation issues.

Some languages incorporate the concept of Friend Class, which can be used instead of meta-programming.

The exception to the exception

Most testing frameworks use meta-programming techniques to collect items to be tested or test cases. For example, xUnit finds all subclasses of TestCcase and all functions that start with testXXX to build test cases.

After many unit tests sooner or later, the need arises to test a private method of a problem domain entity.

In this situation there are two possibilities:

1 Make the previously private method public.

2 Use meta-programming to ‘invoke’ a private method with some reflection mechanism that avoids controls.

But to perform 1) we should start to expose accidental behavior that does not belong to the real entity violating the rule of bijection and regarding 2) many languages do not allow it and it is also a bad design practice.

To solve the dilemma we can check the site shoulditestprivatemethods.com created by the great Kent Beck.

The alternative is to think about the reason for testing a private function. The answer is always that the private function does an internal calculation or models an algorithm.

To solve the dilemma we leave the private method. We extract the algorithm and test it unitary, achieving concept reification (which surely exists in the domain of the problem) and its possible reuse favoring composition. Happy ending.

and we can test it!!

So we did it in tests.

Serialization and persistence can be used with meta-programming because they are not real problems of the domain we are modeling and they should not add “extra behavior” dirtying objects.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

Conclusions

Meta-programming is something we should avoid at all costs, instead of using abstractions that exist in the real-world and that we should only go looking for patiently.

The search for such abstractions takes a much deeper understanding of the domain than what we came out to obtain, and in the face of the need to learn a new domain, programmers in general, due to laziness, we tend to invent gadgets and mechanisms instead of looking for them in the real world.

Part of the objective of this series of articles is to generate spaces for debate and discussion on software design.

We look forward to comments and suggestions on this article.

This article was published at the same time in Spanish here.